Reversible Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: A Dual Technology

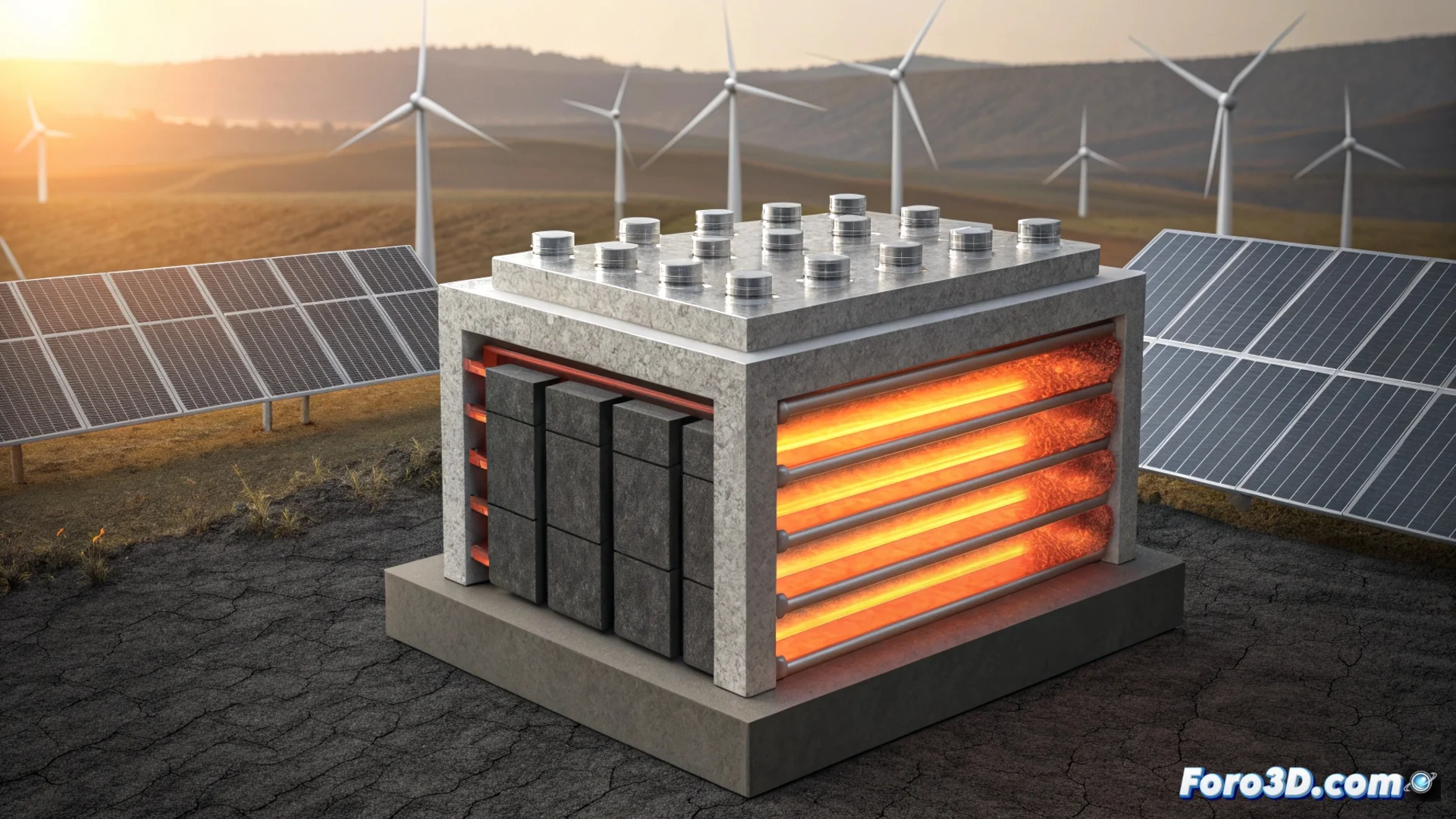

In the landscape of energy technologies, one device stands out for its ability to operate in two opposite directions. This is the reversible solid oxide fuel cell (rSOC). This electrochemical system can switch between generating electricity and consuming it to produce hydrogen, positioning itself as a vital component for balancing grids with high penetration of renewable sources. 🔄

Dual Operation Mechanism

The core of this technology is a specialized ceramic electrolyte. This component conducts oxygen ions but requires operation at high temperatures, generally between 600 and 900 °C. Its versatility lies in its reversible operation:

The two key modes:- Fuel cell mode: Here, the device generates electrical energy. It combines hydrogen with oxygen from the air, releasing electrons that form a useful current and producing water vapor as a byproduct.

- Electrolyzer mode: In this configuration, the system consumes electricity. It applies this energy to decompose water vapor molecules, releasing pure hydrogen on one side and oxygen on the other.

This reversibility makes rSOC systems a fundamental tool for managing the intermittency of solar and wind energy, storing excess as hydrogen and regenerating electricity on demand.

Applications and Challenges to Overcome

The main utility of these cells is large-scale and long-term energy storage. They are ideal for coupling with wind or solar farms. They can also be integrated into existing gas infrastructures to inject hydrogen or act as autonomous backup systems for buildings. However, their massive deployment faces considerable technical challenges.

Current technology challenges:- Material degradation: Repeated thermal and chemical cycles during mode changes wear out the ceramic components, reducing the system's lifespan.

- Complexity of auxiliary systems: Managing residual heat and water vapor flows requires complex and costly subsystems.

- High cost: Specialized ceramic materials and high-temperature infrastructure keep prices high.

The Future of Research

The work of scientists and engineers focuses on two main fronts. The first is to develop more robust materials that better withstand cycle fatigue. The second, and perhaps most crucial, is to reduce the operating temperature. Achieving efficient operation at lower temperatures would allow the use of cheaper materials and simplify thermal management systems, reducing total costs. This technology, in its operational "indecision," could be the key to a more flexible and sustainable energy system. ⚡